Digital Storytelling: A New Paradigm

I’m still mulling over Monica Hesse’s article, “As books go beyond printed page to multisensory experience, what about reading?” It’s packed with so many of the ideas swirling around Vooks and other new digital storytelling formats. Although I scoffed at her rumination (“Is a hybrid book our future? Maybe…“), I actually think that there’s a boatload of substance worth recapping, including an open-ended question about whether digital storytelling formats like vooks will diminish readers’ capacities for imagination.

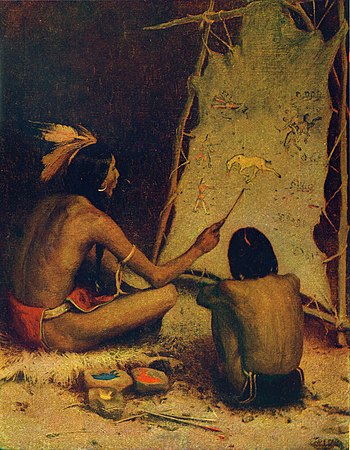

It’s amusing that digital storytelling has been something of a sleeper topic for a decade or more, idling at the margins of publishing and academia. I might be exaggerating slightly, but generally speaking the mainstream publishing chatter has been focused on best sellers, the shift from fiction to non-fiction, online sales, etc. and suddenly — propelled by the rapidly shifting sands of book/media retail and recent innovations in book/media integration, packaging and distribution — everyone’s chattering wildly about the death of the book, the pros and cons of new media, etc. My enthusiasm for the changing publishing landscape is no secret. In fact, ever since I discovered Dana Atchley a decade ago, I’ve been trumpeting the clarion call for multimodal, interactive storytelling. And, despite newer and sexier storytelling possibilities emerging every day due to advances in the multimedia toolbox, increasingly ubiquitous (and ever faster) connectivity, and the digitally fueled appetites and habits of today’s consumers, I’m keenly drawn to the most primitive and basic roots of storytelling.

As the developed and developing worlds hurtle into the age of digital storytelling, it’s more important than ever to remember that the fundamental storytelling ingredients persist. I see a trend toward producing increasingly impressive digital stories that showcase multimedia razzle-dazzle at the expense of good storytelling. Well constructed narrative will always be more important than even the most sophisticated digital storytelling. I hope! And, I also suspect that there will always remain a place for the most basic oral storytelling, even as attentions spans shorten and the magic of digital storytelling enraptures us.

But, let’s cut back to where I left off in a recent digital storytelling post about Monica Hesse’s question: “Is a hybrid book our future? Maybe…” No, not maybe. Of course hybrid books are our future. The unknown is whether or not conventional print publishing will endure. Is a printed book our future? Maybe. That is an important and intriguing question that only time will answer. I’m gambling that the answer is yes, we will continue to print books for a long time. But print books will become the exception, not the norm. Printing books will become a niche market in the publishing industry, catering to very specific needs such as collector’s editions, beautiful coffee table editions of art, design and other expensive format publications.

Monica Hesse continues: “Perhaps the folly isn’t in speculating that the book might change, but in assuming that it won’t.” Bingo! It’s inevitable, so let’s shift the focus of the debate and brainstorming to what I find most exciting about the advent of digital storytelling: its extraordinary potential. Certainly it dilates the potential for producing books, narratives, learning experiences, etc. that span a far broader diversity of learning styles/capabilities while better serving some handicapped audiences. Digital storytelling opens as yet unimaginable non-linear storytelling formats that were simply too challenging (or maybe even too subtle or cumbersome) for print media. It democratizes the publishing world in an exciting, possibly scary or dangerous, and ultimately positive way. It will demand and catalyze long overdue shifts in the way that we teach children to think (both analytically and synthetically), to decipher fact from fiction, to communicate in non-digital contexts, to focus over extended periods of time and a host of ways we haven’t yet conceptualized.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspects of digital storytelling are new avenues for communicating still invisible beyond the horizon. Will we be able to engage more of the senses than just sight and sound? Will we be able to untether digital stories? Will we be able to package multi-format stories that are compatible with multiple devices and accessible in multiple formats (text, audio book, video, multimedia)? Will be able to open up digital books for broader sharing, one of the most practical advantages of print books? What sort of copyright innovations will evolve to track increasingly complicated intellectual ownership stories and story ingredients?

I would encourage authors and producers of digital stories to break free of the rules, conventions and expectations of the last five centuries of book publishing. Don’t just translate books into digital books. Look at the terminology — ebooks, digital books, video books, vooks — for proof that we’re still frozen in the Gutenberg paradigm. Amplify the idea of storytelling. Leverage today’s multimodal communication vehicles by integrating text, audio, video with the vast array of social networking tools so that the texture of storytelling is profound, diverse and malleable. Open storytelling up so that “readers'” experiences can be varied (maybe even unique?) which will compel greater interest, sharing, debate, buzz, marketing, content development.

Digital storytelling must develop the potential for annotation and marginalia that print books permit. And it will be important to devise innovative ways for readers/consumers to share this marginalia. I know this sounds scary, and it poses real challenges (intellectual property rights, etc.), but it is inevitable and good. And it will unleash a viral potential heretofore unfathomable, not to mention the pedagogical implications. I touched on these ideas briefly in a recent post about James Governor’s “Reading is Writing: Illuminating The Digital Manuscript“.

In sum, I agree with Scholastic editor David Levithan: “It’s expanding the notion of what storytelling can be.” Rather than fear and desperation, publishers should be reinvigorated, revitalized and optimistic. The publishing industry should embrace the new digital storytelling paradigm and begin dreaming up creative new storytelling opportunities. Frankly traditional print books represent a single, extremely restricted vehicle for telling stories. Five centuries of increasing ubiquity make it challenging to think beyond the limitations of a stack of paper sandwiched between two covers, but storytelling existed long before the printing press, and it will continue to exist (and flourish) long after books become relics.

Of course, change always introduces new concerns and risks as well. Hesse asks whether reading and imagination will suffer as a result of innovations in digital storytelling. She acknowledges that digital books empower the reader to skip around, perhaps even skip sections altogether. “It’s also possible for the user to never read more than a few chapters in sequence, before excitedly scampering over to the next activity…” This is certainly true, and not only because integration of audio and video invite this sort of jumpy navigation. Searchability alone is revolutionary. The ability to quickly, easily filter a digital text for relevant terms, references, etc. shifts significant control from the author/publisher to the reader. This basic change invites us to leap from relevant topic to relevant topic rather than trudging from beginning to middle to end. But is this a problem? It could be if authors think and write according to the conventional Gutenberg paradigm. But authors can evolve and grow. In fact, many may welcome the change, may recognize its vast potential. Inevitably some will not.

“Hybrid books might be the perfect accessory for modern life. They allow immediate shortcuts to information. They feel like instant gratification and guided, packaged experiences. What they don’t feel like, at least in certain examples, is reading.“

Although there’s reason aplenty to fret the diminishing attention spans of people increasingly plugged into a digital world, I’m not convinced that the “feeling of reading” is in and of itself critical. Some of us love to grab a book and tuck into a hammock on a summer afternoon. It’s pretty hard to beat this “feeling of reading”, but I’m not terribly concerned that fewer and fewer people seem to desire it. It does concern me that a reduction in reading might indicate a reduction in the type of thinking and protracted focus that reading fosters. But I’m not convinced that a shift from print to digital storytelling is the culprit, especially of a potential loss of imaginative thinking which is encouraged by reading a print book. Television and video/movie consumption seem more likely culprits. (Or an ever more pervasive culture of instant gratification?) But the sort of digital storytelling I’m aspiring toward is a far cry from a video or a television program.

Vook’s founder, Brad Inman discourages us from equating print books and Vooks, emphasizing that the two storytelling formats are unique. “‘We don’t pretend that it’s a book because it’s not.’ With the Vook, ‘there’s an expectation that you’re not gulping the text,’ as you would in a traditional novel. Instead, Inman says, ‘you’re tasting the text,’ dipping in and out of it at will.”

I think that this in-and-out experience is potentially one of the great values of digital storytelling. Although Hesse cites Clifford Nass, a Stanford professor who studies multitasking, to distinguish between active and passive entertainment when reading or watching a video, we need to remember that digital books are not videos. Even vooks are not videos. Watching a video or a movie or a television program is considerably more passive than reading the same content, and I agree that the reader is more engaged, more thoughtful and more imaginative than the passive viewer of video. But in digital storytelling, video is only one of the modalities employed to advance the narrative. Although type and depth of imagination employed when reading a print book certainly is different from reading, a well composed digital book is not a passive experience. Indeed it should be considerably more interactive than a print book precisely because of the in-and-out experience which empowers the reader to elect, decision after decision, a personal experience within the narrative, ideally participating on some level and sharing at will. Think more seminar, less lecture. Perhaps Hesse’s reaction tells us more about the shortcomings of a specific vook rather than digital books in general.

“In reading “Embassy,” what concerned me wasn’t that my brain was getting overworked but that my imagination wasn’t… when the “true” representation… is immediately provided to the reader, imaginary worlds could be squelched before they have a chance to be born. Reading Vooks made me feel a little like a creative slacker…”

Like Clifford Nass, David Sousa (an educational neuroscience consultant who wrote “How the Brain Learns to Read”) is likely correct in his concerns about the effects of video on the imagination of children, it is less helpful when evaluating digital storytelling: “we find that kids are not able to do imagining and imaging as exercises… because video’s doing the work for them… They still have the mental apparatus for that, the problem is they’re not getting the exercise.”

However, digital storytelling is not video. It profits from the integration of video into a considerably more interactive tapestry of narrative that engages the reader at every turn, offering multiple levels of interaction and a great deal of independence for how to navigate the content. Digital storytelling at its best should challenge the imagination more consistently and more rigorously than video and likely than conventional print books. Perhaps we’re not there yet. Certainly we’re not there yet. We’re at the proverbial dawn of a new storytelling paradigm, and it’s only logical that the prototypes will be awkward prototypes. But they offer an exciting glimpse into the future, a future that will be driven by raconteurs creating for the new paradigm, not just trying to adapt or salvage the Gutenberg paradigm.

Hesse shares this open-minded optimism, concluding with Bog Stein’s inspiring outlook. “‘Things like the Vook are trivial. We’re going to see an explosion of experimentation before we see a dominant new format. We’re at the very beginning stages’ of figuring out what narrative might look like in the future. ‘The very, very beginning.'”